Why Republican Party Leaders Matter More Than Democratic Ones

The Difference Between Patronage and Constituent Parties

The Republican and Democratic parties are not the same: power flows differently within them. The two big political news items of this week—the happenings of the Republican National Convention and the desperate attempts of many Democrats to replace their candidate before their own convention next month—reflect these asymmetries. Nevertheless, many discussions of American politics assume that the structures and operational norms of the two parties are the same. If these party differences were more widely recognized, I suspect we would see fewer evangelicals frustrated with their limited influence over the GOP party platform, fewer journalists shocked with J.D. Vance’s journey from never-Trump land to MAGA-maximalism, and greater alarm among centrist Democrats about the longer-term influence that the Palestine protests will have on the contours of their coalition.

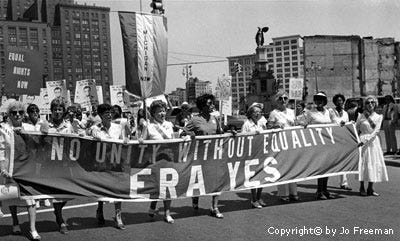

My perspective on all this has been strongly shaped by two research articles penned by political scientist Jo Freeman.1 In her youth Freeman was a new left activist, one of the founding activist-intellectuals of feminism’s second wave. She is perhaps most famous today for two essays she wrote in her activist days (both under her movement name “Joreen”). The first, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” is a biting critique of the counterculture dream of eliminating hierarchy from activist organizations. The second, “Trashing: the Dark Side of Sisterhood,” is one of the original descriptions of “Cancel Culture.” There Freeman provides a psychological account of how cancellation (she calls it “trashing”) works and the paralyzing effect it has within leftist organizations, where cancellations are most common.2 If you have never read these essays I recommend you do. Freeman’s internal critiques of left-wing movements at work are more insightful than most rightwing jeremiads against them.

Neither of these essays shed much light on the Republican Party. For that we must turn to her later, more academic work. In particular, her 1987 article “Who You Know vs. Who You Represent: Feminist Influence in the Democratic and Republican Parties,” and her 1986 “The Political Culture of the Democratic and Republican Parties.”

Freeman’s academic interests were framed by her activist experiences. She was deeply involved in the seventies attempts to get feminist planks onto the Democratic and Republican party platforms. Up to that juncture the Republican Party had far stronger feminist credentials than the Democrats did; had the feminist of 1960 been forced to predict which party would champion her cause thirty years later, she would have guessed the GOP.

This is not what happened. That is the mystery that drives much of Freeman’s late ‘80s work: why did the feminist movement succeed so brilliantly with the Democrats, but fail so miserably with the Republicans? Freeman argues that this had less to do with demographics or deep ideological alignment than with the structures and operational culture of each party. Although both parties have changed in the days since Freeman stalked the convention floors, many of the differences she observed between the two parties still hold true today.

The place to start is a 1980 vote on the floor of the Democratic National Convention. That year the primary feminist organizations working the convention hall were the National Woman’s Political Caucus (NWPC) and the National Organization for Women (NOW). Their pet cause was the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The Democrats had already endorsed the amendment, so NOW and the NWPC decided to up the ante: they would support a party plank that read “the Democratic Party shall offer no financial support and technical campaign assistance to candidates who do not support the ERA.” This measure, known as Minority Report #10, became the focus of their efforts.

Jimmy Carter’s delegates controlled the floor. Though no enemy to feminism, his team thought Ten was ill advised. The Democrats’ existing support for the ERA was robust, Carter balked at draconian single-issue “loyalty tests” that might erode his shaky coalition, and he did not wish to make feminist issues central to his campaign. He had the numbers to defeat this change. NOW and the NWPC understood this. Knowing full well that they could not win, the feminist groups decided to push for a floor vote anyway. The vote went just as expected. They lost the floor fight. The Democratic platform did not change.

What did this public defeat portend for the movement? Victory. Losing the fight on the floor did not set the movement back an inch. Far from it: at the next convention these same women’s organizations were given a greater share of decision making authority. All potential presidential candidates courted NOW’s endorsement months before the 1984 convention began; their preferred amendments were incorporated into the platform without issue. “Because feminists got pretty much everything they wanted prior to the Democratic Convention,” Freeman comments, “there wasn’t much to do there except celebrate.”3

This is somewhat mysterious. The feminist movement leaders sought an intentional defeat—but only gained power because of it.

We still see this story play out on the left today. Though the contest for clout has shifted out of the convention halls and out onto social media, when you look at the trajectory of leftist movements over the 2010s—such as the Black Lives Matter movement—you find a similar pattern. Protests that closed with policy defeat, changing nothing but media coverage, did not lead to the marginalization of protest leaders or their moment. Quite the opposite: with each defeat the influence these movements held over the Democratic establishment grew.

Why does this happen? Freeman argues that peculiar features of Democratic Party organization and political culture allow activists to profit from defeat. Here is how she describes the salient Democratic Party features:

Both parties are composed of numerous units, which have a superficial similarity… In addition to these formal bodies, the Democratic Party, especially on the national level, is composed of constituencies. These constituencies see themselves as having a salient characteristic creating a common agenda which they feel the party must respond to. Virtually all of these groups exist in organized form independent of the Party and seek to act on the elected officials of both parties. They are recognized by Democratic Party officials as representing the interests of important blocs of voters which the Party must respond to as a Party. Some groups have been recognized parts of the Democratic coalition since the New Deal (e.g. blacks and labor); others are relatively new (e.g. women and gays). Still others which participated in State and local Democratic politics when those were the only significant Party units have not been active as organized groups on the national level (e.g. farmers ethnics).

Some of the Party’s current constituencies have staff members of the Democratic National Committee identified as their liaisons. In addition, in the last few years an informal understanding has arisen that one of each of the three Vice-Chairs will be a member of and represent women, blacks and hispanics. Labor — still the largest and most important constituency — does not feel the need for a liaison as it has direct contact with the party chair. However, a majority of the 25 at-large seats on the DNC, as well as seats on the Executive Committee and the Rules and Credentials Committees at the conventions are reserved for union representatives. Party constituencies generally meet as separate caucuses at the national conventions. Space for these meetings is usually arranged by the DNC. While caucuses are usually open to anyone, the people who attend are generally those for whom that constituency is a primary reference group; i.e. a group with which they identify and which gives them a sense of purpose. With an occasional exception the power of group leaders derives from their ability to accurately reflect the interests of constituency members to the Party leaders. Therefore, while leaders are rarely chosen by the participants, they nonetheless feel compelled to have their decisions ratified by them through debate and votes in the caucuses. The votes usually go the way the leaders direct, but they are symbolically important.4

For Freeman the most important fact about the Democratic Party is that its representative constituent groups exist in an organized form independent of the party apparatus proper. This means that the position (and to a lesser extent the power) of the men and women who lead these constituencies is not dependent on the favor of party leaders. To the contrary, Democratic Party leaders tend to think of their personal power as being dependent on the support of the constituencies the activist leaders represent.

This has two important implications. The first is that the power and career success of Democrats who either lead or strongly identify with a minority constituency “is tied to that of [their minority] group as a whole. They succeed as the group succeeds. When the group obtains more power, individuals within that group get more positions.”

Democratic leaders think of their party as a bargaining table: various groups looking for representation in the Democratic Party come to this table, demonstrate what they can do for the party, demand that the party do something for them in turn, and negotiate with competing constituencies on matters of policy and personnel. The more electorally important an identity group is, the more personnel slots it will generally receive.

The preceding paragraph is an imperfect model of actually existing Democratic politics—but it is the mental model of Democratic politics that Democratic politicians use as a reference point when evaluating the real thing. Ideals shape behavior. In this case, the ideal model makes Democratic politicians sensitive to signals of commitment and cohesion on the part of potential constituencies.

In other words: activist leaders have much to gain from making a ruckus. Every brouhaha an activist can foment shows that the constituency they claim to represent is real—and must be reckoned with. As Freeman puts it:

In the Democratic Party, keeping quiet is the cause of atrophy and speaking out is a means of access. Although the Party continues to be one of multiple power centers with multiple access points, both the type and importance of powerful groups within it has changed over time. State and local parties have weakened in the last few decades and the influence of national constituency groups has grown. The process of change has resulted in a great deal of conflict as former participants resist declining influence (e.g. the South, Chicago’s Mayor Daley) while newer ones jocky for position (women and blacks). Successfully picking fights is the primary way by which groups acquire clout within the Party.

Since the purpose of most of the conflict is to achieve acceptance and eventually power it does not matter whether the issues that are fought over are substantive or only symbolic. In the 1950s and 1960s these fights were usually over credentials as southern delegations were challenged because of their refusal to declare their loyalty to the national ticket and their inadequate representation of blacks. In the 1970s and 1980s, the fights have usually been over platform planks but some have concerned rules changes or designations of status. In 1976 Women’s groups fought over the “equal division” rule to require that half of all delegates be women. Although they lost, they had to find another issue in 1980 because the DNC decided to adopt it 1978. Instead they focused on minority planks on abortion and denying Party support to opponents of the ERA. In 1984 the issue would have been a woman Vice Presidential candidate, but this was preempted by Walter Mondale’s selection of Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate so there was nothing to fight over.5

This leads to the second implication of the Democrats bottom-up structure. It is not always obvious who speaks for a given constituency. Activists and group leaders thus not only need to pick fights that demonstrate the importance of their group, but also need to pick fights that cement their legitimacy as representatives of this constituency. Freeman points to Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential run as a case in point:

Jesse Jackson’s entire campaign was a way for a new generation of Black leaders to establish clout both within the Party and within the Black community. The means by which Blacks have exercised power in the Party has been less through organizations than through elected officials and their individual followings. As there is no internal mechanism for selecting leaders among the many contenders, those Blacks who have exercised power within the Party have usually been those whom White party leaders chose to listen to. Jackson’s candidacy challenged both the current Black political leadership and the right of Whites to decide which Blacks were legitimate leaders. By showing that Black voters would unite behind his candidacy in the primaries he established his legitimacy as a national Black spokesperson, independent of White approval. This gave him a claim to dictate the Black agenda in the Party, even though he had not previously been a Party activist and there were many competent Black leaders within the Party who were not supportive of this upstart.6

This is why the feminist maneuvers in the 1980 convention made sense: whether the feminists won the floor fight was less important than demonstrating that the women’s groups were a constituency capable of forcing a floor fight in the first place. The activists lost their battle, but successfully proved that their army could be mustered, and that its soldiers looked to them for marching orders. They demonstrated that they deserved a larger spot at the negotiating table—and during the next convention they were given one.

The Republicans are different. In the ‘70s and ‘80s Republican feminists refused to bring losing battles to the floor. Where most Democratic activists view their constituency identity as primary and their party identity as secondary, most of the Republican feminists Freeman worked with saw themselves as Republicans first. Many were the wives of sitting Republican officials. They were not outsiders clamoring for clout but insiders maneuvering for influence. Their party worked in a very different way from the Democrats:

The basic components of the Republican Party are geographic units and ideological factions. Unlike the Democratic groups, these entities exist only as internal party mechanisms. The geographic units—state and local parties— are primarily channels for mobilizing support and distributing information on what the Party leaders want. They are not separate and distinct levels of operation.

Ideological factions are also not power centers independent of their relationship to Party leaders. Unlike Democratic caucus leaders, Republican faction leaders do not feel themselves accountable to their followers. Sometimes there are no identifiable followers… The purpose of ideological factions—at least those that are organized— is to generate new ideas and test their appeal. Initially these new ideas are for internal consumption. Their concept of success is not winning benefits, symbolic or otherwise, for their group, so much as being able to provide overall direction to the Party.

…The Republican Party does have several organized groups within it such as the National Federation of Republican Women, National Black Republican Council and the Jewish Coalition, but their purpose is not to represent the views of these groups to the party. Their function is to recruit and organize group members into the Republican Party as workers and contributors. They carry the party’s message outward, not the group’s message inward. Democratic constituency group members generally have a primary identification with their group, and only a secondary one with the Party. The primary identification of Republican activists is with the Republican Party. They view other strong group attachments as disloyal and unnecessary.7

The Republicans of Freeman’s era did not attend caucuses. They attended receptions. “These receptions are usually closed — by invitation only. Invitations may not always be hard to obtain, but they are required.” Like caucuses, receptions are an opportunity to display status. Unlike Democratic caucuses, status is not about signaling constituent support. Those honored are so honored by invitations and public acknowledgement from important party leaders. Receptions “are places to network; to be seen and to get information. If one wishes to exercise influence, it is best to arrange an introduction to a recognized leader by a mutual friend.”8

This is because the Republican party is fundamentally a leader oriented political organization. Power flows from the top down. Convention battles were not contests between constituencies, but contests between patronage networks. The party is organized around powerful leaders and those who fly their colors under their patron’s banner:

Legitimacy within the Republican Party is dependent on having a personal connection to the leadership. Consequently, supporting the wrong candidate can have disastrous effects on one’s ability to influence decisions. Republican Presidents exercise a monolithic power over their party that Democratic Presidents do not have. With the nomination of Ronald Reagan, many life-long Republicans active on the national level who had supported Ford or Bush had to quickly change their views to conform to those of the winner or find themselves completely cut off. Mavericks, who do not have any personal attachments to identified leaders, may be able to operate as gadflies, but can rarely build an independent power base. Since legitimacy in the Democratic Party is based on the existence of just such a power base, real or imagined, one does not lose all of one’s influence within the Party with a change in leaders as long as one can credibly argue that one represents a legitimate group.

While the importance of personal connections works against those Republicans who have the wrong connections it rewards those who spend years toiling in the fields for the Party and its candidates. The longer one spends in any organization the more personal connections one has an opportunity to make. These aren’t lost when one’s Party or leaders are out of power, and thus can be “banked” for future use. Occasionally a dedicated party worker can develop sufficient ties even to competing leaders to assure continued access, if not always influence, regardless of who’s in power. Those Democrats whose legitimacy derives from leadership of a coalition group find it is quite transitory when they can no longer credibly represent the group. The greater willingness of the Republican Party to reward loyalty and dedication to the Party in preference to any other group makes it is easier for the Party to discourage extra-Party attachments.9

Traditionally the Republicans saw themselves as the standard bearers of the American norm. Their lifestyle was the generic American lifestyle; their voters were the largest single demographic bloc in America. Where Democrats self-consciously saw themselves as representing diverse groups with diverse and even conflicting interests, Republicans thought of themselves as trustees for the shared national interest.10 Their job was to act in the best interests of the American whole.

Freeman suggests that Republicans took a similar view of the Grand Old Party itself:

The Republican party sees itself as an organic whole whose parts are interdependent. Republican activists are expected to be “good soldiers” who respect leadership and whose only important political commitment is to the Republican Party. Since direction comes from the top, the manner by which one effects policy is by quietly building a consensus among key individuals, and then pleading one’s case to the leadership as furthering the basic values of the party. Maneuvering is OK. Challenging is not.

This approach acknowledges the leadership’s right to make final decisions and reassures them that those preferring different policies do not have competing allegiances. On the other hand, open challenges or admissions of fundamental disagreements indicates that one might be too independent to be a reliable soldier who will always put the interests of the Party first. This cuts off access to the leadership and thus is quite risky—unless the leadership changes to people more amenable to the challengers. While not risky like an open challenge, quietly building an internal consensus is nonetheless costly of one’s political resources. Activists learn early to conserve their resources by only contesting issues of great importance to them.11

This is one reason why the Republican feminists of the 1970s took a decidedly less confrontational approach than their Democratic sisters. This is also why they faced so many setbacks. The Republican feminists were closely tied to the administration of Gerald Ford. Power flowed down to them from their connections to the man up top. When that man was replaced, they had no independent power base to retreat to and were shoved out of the party.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both operational cultures. “In the short run [Democratic political culture] appears disruptive,” Freeman argues, but in the long run “it is more stable. Once a consensus develops about the desirability of a particular course of action, whether it be programmatic or procedural, it is accepted as right and proper and is not easily thwarted by party leaders, even when one of them is the President.” In contrast, “the Republican Party is more likely to change directions when it changes leaders.”12

Is there a better example than the ascension of Donald Trump? The GOP was once a party of full of men like J.D. Vance, eager to condemn Trump as the American Hitler. The GOP is now a party full of men… like J.D. Vance, eager to fête Trump as the savior of the Republic. How could this happen? The Republican Party offers neither power nor refuge to those who have not hitched their cart to its reigning star. A Republican Party that won in 2012 or lost in 2016 would look fundamentally different—much more fundamentally different than a Democratic Party helmed by Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders instead Obama or Biden. The ability of democratic presidents to reshape their party is limited unless, like FDR, they bring in a new suite of constituencies to the coalition.

This causes some difficulties for identity based constituencies subsumed in the republican hierarchy. Consider the waves of discontent we see emanating from evangelicals in the wake of the Republican National Convention. Their upset is understandable: All of the evangelical policy priorities have been dropped from the platform; the presence of Sikh prayers and stripper speakers seem like an intentional snub to a loyal part of the Trump coalition. These complaints are not really new. For three decades evangelicals have wondered why their priorities have not been given the same weight in Republican politics that similarly sized constituent groups (such as Hispanic or Black Americans) are given in Democratic circles. I trust you now see the answer: the Democrats are organized in a fashion that forces them to give undue attention to small constituency groups. Neither the organizational forms or political culture of the Republican Party offer the same advantage to American evangelicals.

It is possible this structure may change in the future. From the 1860s forward Republican Party leaders governed secure in the belief that they defended the American mainstream. In the late 20th century that meant middle and upper-middle class white families. That demographic is not as aligned with the Republicans as it was in the pre-Trump era; the upper-middle class now defaults Democrat. Moreover, the relative share of the population occupied by the old American core is shrinking. In many states it is already a plurality demographic. Increasingly, Republicans see themselves not as defenders of the American mainstream but as the tribunes of the American outcasts.

Some on the right wing would prefer if the GOP adopted Democratic forms. This would mean framing itself as a coalitional party like the Democrats with formally recognized constituencies whose interests must be explicitly catered to. In this vision the white working class would become the most important of these constituencies.

Freeman’s analysis suggests why it will be difficult for the Republicans to follow this path. It will be hard enough for the GOP to abandon an operational culture a century and a half old. It will be harder still to restructure the party apparatus itself, building out caucus-like civic organizations to represent the interests of its constituencies. At the moment it simply is not clear which organizations or individuals might represent the white working class within party circles; with the exception of the evangelicals, most of the potential Republican constituencies lack the group-consciousness needed for Democratic style politics. No GOP leader would wish to create these groups himself—it would mean siphoning away his power. As long as power flows downwards in Republican politics there will be little incentive for Republican leaders to change the system.

It is not clear the party as a whole would benefit from doing so. The Biden succession drama points to the weaknesses of a bottom-up party structure. Unity is much more difficult to achieve in the Democratic Party. The structure and culture of the party encourages small disputes to metastasize. Democratic Party leaders do not want to abandon Biden for the same reasons no one wanted to run against him in the primaries: when fissures in the Democratic Party open, they are difficult to close again. After fighting, the Republicans get back in line; those who will not do so are sidelined. They lack an external base of power to keep up the fight. For Democrats things are different—only the threat of electoral defeat keeps them cohesive. “Ridin’ with Biden” is an easy Schelling point. Remove that point and the knives will come out. Few Democratic politicians imagine they will fare well in a late season knife fight. With a party structure this fissiparous, they are probably right.

—————————————————————-

If you found this post worth reading, you might find some of my other essays on politics and history worth your time. In addition to the pieces written linked to above, check out “Culture Wars are Long Wars”, “The Problem of the New Right” “Further Notes on the New Right,” ” Scrap the Myth of Panic,” and ““On Sparks Before the Prairie Fire” . To get updates on new posts published at the Scholar’s Stage, you can join the Scholar’s Stage Substack mailing list, follow my twitter feed, or support my writing through Patreon. Your support makes this blog possible.

—————————————————————-

Jo Freeman, “The Political Culture of the Democratic and Republican Parties,” or. published in Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 3, Fall 1986, pp. 327-356 (extended version on jofreeman.com); “Who You Know vs Who You Represent: Feminist Influence in the Democratic and Republican Parties,” or. published in The Women’s Movements of the United States and Western Europe: Feminist Consciousness, Political Opportunity and Public Policy ed. by Mary Katzenstein and Carol Mueller, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987, pp. 215-44.

Jo Freeman [“Joreen”], “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” Ms., July 1973, pp. 76-78, 86-89; “Trashing: the Dark Side of Sisterhood,” Ms., April 1976, pp. 49-51, 92-98. Both essays have been republished at greater length at jofreeman.com.

My account is based on Freeman, “Who You Know vs Who You Represent: Feminist Influence in the Democratic and Republican Parties.”

ibid

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

Freeman cites evidence of these self conceptions stretching back into the 1940s and 1950s; Matt Grossmann and David Hopkins reach the same conclusion based on interviews conducted in the 2010s. Their research is presented in ”Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats: The Asymmetry of American Party Politics.” Perspectives on Politics (2015), Vol. 13, No. 1, 119-139.

ibid.

RNC - the church + grifters

DNC - Feudalism + sharecroppers

This reflects the money flows. The left has many sources of money, patronage, and a variety of supporting institutions, and their political structure mirrors this. People are bringing their own chips to the table.

The right has none of this. No supporting institutions. So the entire infrastructure depends on the party itself.