Two items of interest passed through my feeds this week. The first is the podcast Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz released to explain why they are endorsing Trump for president. The second is an evocative and viral internet advertisement for Careers Built to Last, a slick recruiting website trying to attract young workers to production lines in the maritime industrial base. If you have not seen the ad yet, please watch it now:

I have not been able to stop thinking about this ad since it hit my Twitter feed. It is one of those rare pieces of corporate media that catches a rising zeitgeist. In one minute and thirty seconds it distills a nation’s discontent with the present and a nation’s dreams for the future.

Both our gloom and our hope are tied to our relationship with technology.

In its own way this is also the topic of Andreessen and Horowitz’s podcast. The two venture capitalists declared some time ago that they would base their future endorsements purely on their assessment of the impact that the candidate’s actions might have on emerging technologies (and the start-ups that are attempting to develop and leverage them). This is their “little tech agenda.” Over the course of the episode they explain how this agenda has been harmed by the Biden team’s approach to economic policy. Their objections to the administration are substantive and technical: they point to the administration’s executive order on AI, Biden appointees’ approach to crypto regulation, and Biden’s proposal to tax unrealized gains as mortal threats to the current start-up ecosystem.

Most pertinent to our discussion today, however, is their broader preface to this entire discussion. Their endorsement would have shocked the Andreessen and Horowitz of 2008. In that year both Andreessen and Horowitz were loyal Democrats. Before they could even think about endorsing Trump they had to first become alienated from their old coalition.

Here is how they describe their alienation from the liberal-left:

MA: I actually endorsed Hillary Clinton in 2016 publicly for what I thought were a variety of good reasons. And the way I would describe it is, I’m Gen X, I kind of came of age in the 90s as an entrepreneur. Almost everybody I knew, including myself, just took it for granted, which is like, of course, you’re a Democrat. Of course, you support the Democratic president. And the answer is the formula resolves to an easy answer, which is the Democrats in those days, you know, presidential level were pro-business, they were pro-tech, they were pro-startup. They were pro-America winning in tech markets. They were pro-entrepreneurship. And so you could start a company. They were pro-business. You could be in business. You could be successful in business. You could make a lot of money. And then you give the money away in philanthropy and you get enormous credit for that. And, you know, it absolves you of whatever.

BH: Yeah, well, I was going to say, like, it’s obvious you’re to be a Democrat because you have to be to be a good person. That’s kind of the underlying thing.

MA: But specifically successful business people could then basically become successful philanthropists. This is the path that Gates and many others kind of carved out. And then you could be progressive on social issues, and you could be on the right side of all these sort of societal changes that people were kind of focused on at the time. And the whole thing just seemed completely obvious and completely easy. So I was kind of on that path, frankly, quite strongly through at least 2016.

In retrospect, it’s like there were glimmers of, I’d say, growing anti-tech, I would say animus, probably in the early 2010s. And there were growing kind of anti-business sentiments. And then by the way, something that really disturbed me a while back is sort of growing anti-philanthropy sentiments, which we probably won’t discuss it like today.

BH: Oh, well, yeah. Well, with people who made a lot of money, who gave money away, got criticized for giving money away to charitable causes as opposed to paying more taxes. Kind of a funny life jealousy taken to the extreme, yeah.

MA: A specific moment that happened to me to make me realize the landscape was shifting was when Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan set up the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative where they literally committed to 99 of their assets going to the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative, there was a political faction that basically heavily criticized them, and the theory, number one is to your point, the theory was that they should they should pay it in taxes and the government should distribute the money, they shouldn’t have any control over where it goes, but the other was oh they’re only doing it for a tax break.

BH: Yeah, which wasn’t true.

MA: Well, it can be. It can’t be true because you’re giving away 99% of your assets to get a tax break. Like it literally doesn’t make sense.

BH: It’s like people bad at math and jealous.

MA: Exactly. And so like basically like that formula started to break down. And so, you know, I think like a lot of us in tech, it’s been a much more difficult puzzle to try to figure this all out over the over the last eight years and then particularly over the last four years.1

Andreessen and Horowitz describe an implicit contract between technologists and progressive politicians. Consumer technology was seen as a progressive force in world affairs. The technologist was unlike the CEO of an energy or defense company; he was not a merchant of industrial misery. Provided he acted philanthropically with his vast wealth, this would be recognized. The tech billionaire would be treated as a worthy member of the liberal coalition— a member who deserved his fortune. The breakdown of this contract circa 2016 was a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for Andreessen and Horowitz’s move towards Trump.

As both Kelsey Piper and Ben Thompson note, the notion that “there was a deal and it has broken down” is not new to 2024, nor is it restricted to Andreessen and Horowitz.2 This idea is widespread in the tech brotherhood. Seen from Silicon Valley the 2016 election of Donald Trump was the watershed: liberals unfairly blamed Facebook for Trump’s election, socialist activists began attacking billionaires for giving their wealth away, and aggressive hostility towards all things tech became the default attitude of the press. Among the technology brotherhood, this “techlash” is usually attributed to exogenous events such as the Great Awokening or the shock of Trump’s victory. Less commonly, the culprit is identified as petty jealousy—especially on the part of Ivy League graduates who went into low-paying professions like academia or journalism while their brighter classmates went to San Fransisco. You will find both of these explanations offered in Andreessen and Horowitz’s podcast.

But there are other reasons the American people were primed for a techlash in 2016. One is a matter of scale. In 2016 Andreessen and Horowitz’s industry mattered in a way it did not ten years earlier. Much is asked of those who have been given much. Scrappy start-ups and national champions are treated differently—and should be.

Andreessen and Horowitz recognize this. Their entire “small tech” branding is an attempt to differentiate what they are doing from the vilified “big tech” companies seen in the graphic above. Were the problem simply a matter of size that might have been enough to shift attitudes in their favor.

But size is not consumer tech’s only problem.

This brings us back to the advertisement for welders and machinists.

In that ad the welder’s job is contrasted with “the gig.” The novelty of the gig is an illusion: Part-time jobs are not new to American life. Side hustles have existed for millennia. What is new are side hustles policed by a dinging computer in your pocket. The parade of horribles that Rosie must live through exist only because of the innovators working in Silicon Valley.

The Silicon economy, as this ad imagines it, is precarious yet suffocating. Everything about the system is capricious—and inescapable. The modern worker, it suggests, has been reduced to a small piece of a great cybernetic scheme, a cog in a machine that strips away her freedom even as it makes her paycheck dependent on the whims of strangers.

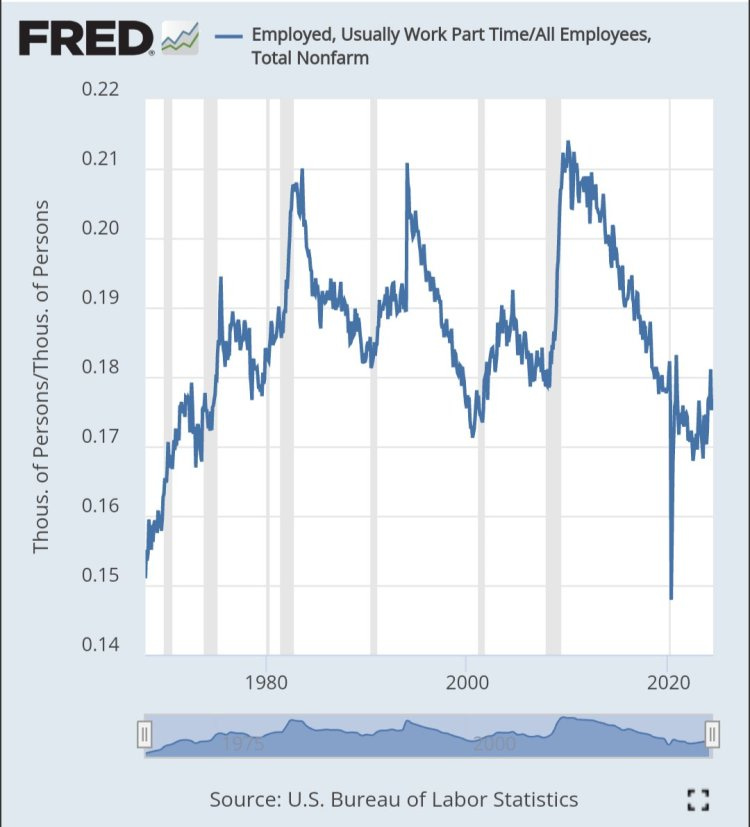

There are good reasons to think that this image of the gig economy is more projection than description. The number of Americans who have ever worked a ‘gig’ is actually fairly small, and the percentage of Americans surviving off of part-time work shrunk over the 2010s.

Consumer tech made greater inroads into social life—in the age of Instagram, Tinder, and TikTok it is natural to feel like a slave to the algorithm. These emotions should not be dismissed. It matters that the average American associates the great software giants with feelings of lost agency.

This was not the original vision of Silicon Valley. With new communication technologies would come a new way of life. We were promised an electronic frontier, an escape from the confines and hierarchies of the industrial world, a new “civilization of the mind” unencumbered by the petty rules of a dying past.3 A computer in every pocket would ennoble the masses. It offered anyone, anywhere the sort of freedom once reserved for the few.

That was the dream. Things did not quite turn out that way. So far have we strayed from that vision that the proposed solution to our ills is…. to escape our software shackles by becoming a line worker in the American military-industrial complex!

The ad is more an exercise in rhetoric than depiction of reality, of course. It has an agenda. That agenda has no interest in fairly depicting the digital economy. Nevertheless, the ad resonates. There is enough overlap between life imagined and life experienced for this little video to go viral.

It is to that overlap, I think, we must look in order to understand why the implicit contract between tech and the rest broke apart. Software will “eat the world,” we were told.4 We trusted all of this devouring would leave the world a better place. By 2016 or so our nation could see this new world emerging. It did not seem much like the promised better place. Uber is a poor replacement for utopia.4

I suspect that this, not Trump’s election, or the Great Awokening, or the jealousy of ten thousand journalists, was the most important source for the “techlash” that followed.

————————————————————-

Your support makes this blog possible. To get updates on new posts published at the Scholar’s Stage, you can join the Scholar’s Stage Substack mailing list, follow my twitter feed, or support my writing through Patreon. If you found this post worth reading, you might find some of my other essays on science, technology, and modern life worth reading. In addition to the pieces written linked to above, check out “American Nightmares: Wang Huning and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Dark Visions of the Future,” “Has Technological Progress Stalled?,” “Thoughts on Post Liberalism,” and “Lessons from the 19th Century.”

—————————————————————-

Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen, The Ben and Marc Show (video podcast), “The Little Tech Agenda: Biden vs. Trump,” 16 July 2024.

I have taken the transcript from Ben Thompson, “Tech For Trump, Breaking the Deal, From Inertness to Interest,” Stratechery (17 July 2024).

Thompson, “Tech for Trump”; Kelsey Piper, twitter thread, 16 July 2024.

John Parry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, 8 February 1996.

Marc Andreessen, “Why Software Is Eating the World,” Wall Street Journal, 20 August 2011.

Great analysis, and definitely agree in terms of the promise vs reality of where tech took us—including the vision before of millions of small businesses with the inherently decentralized internet, vs the tech titans that are now much of the total stock market alone (and individually are larger in value than entire countries’ GDP).

That’s part of the small vs big tech too, and people can be forgiven for not really seeing the difference when the original promise of what the future looked like from what used to be “small tech” also turned out not to be.

IMO the Tech Backlash started around 2014 when the NYT figured out that they are actually competitors in the digital market against Google and Facebook and their previously glowing coverage of Silicon Valley turned into daily attacks. By 2018 they were criticizing the stray cats at Googleplex. This was part of their successful digital transformation strategy.