Though much may separate Thucydides, Xenophon, Ephorus, Plato, and Aristotle from one another, on this fundamental point they and those who subsequently followed their lead were agreed: that to come to understand a polity, one must be willing to entertain two propositions.

First, one must presume that the form of government, the constitution, the rules defining membership in the políteuma or ruling order is the chief determinant of a political community’s character. Second, one must assume that paıdeía, which is to say, education and moral formation in the broadest and most comprehensive sense, is more important than anything else in deciding the character of a particular polıteía. In one passage of The Politics, Aristotle suggests that it is the provision of a common paıdeía—and nothing else—that turns a multitude into a unit and constitutes it as a pólıs; in another, he indicates that it is the polıteía which defines the pólıs as such. Though apparently in contradiction, these two statements are in fact equivalent—for, as the peripatetic recognized, man is an imitative animal, the example we set is far more influential than what we say, and it is the “distribution and disposition of offices and honors [táxıs tōˆn archōˆn]” constituting the políteuma of a given polity that is the most effective educator therein.

…what really matters most with regard to political understanding is this: to decide who is to rule or what sorts of human beings are to share in rule and function as a community’s políteuma is to determine which of the various and competing titles to rule is to be authoritative; in turn, this is to decide what qualities are to be admired and honored in the city, what is to be considered advantageous and just, and how happiness and success [eudaımonía] are to be understood and pursued; and this decision—more than any other—determines the paıdeía which constitutes “the one way of life of a whole pólıs.”

—Paul Rahe, The Spartan Regime: Its Character, Origins, and Grand Strategy, xii-xiv.

I often draw a distinction between the political elites of Washington DC and the industrial elites of Silicon Valley with a joke: in San Francisco reading books, and talking about what you have read, is a matter of high prestige. Not so in Washington DC. In Washington people never read books—they just write them.

To write a book, of course, one must read a good few. But the distinction I drive at is quite real. In Washington, the man of ideas is a wonk. The wonk is not a generalist. The ideal wonk knows more about his or her chosen topic than you ever will. She can comment on every line of a select arms limitation treaty, recite all Chinese human rights violations that occurred in the year 2023, or explain to you the exact implications of the new residential clean energy tax credit—but never all at once.

The operatives and the media men of DC are of a different species. They will freely talk of anything, regardless of how much they know about it. But by and large the pundits and politicos are not intellectuals, and little intellectual work is expected of them. Those who love ideas for their own sake travel the path of the credentialed expertise.

Washington intellectuals are masters of small mountains. Some of their peaks are more difficult to summit than others. Many smaller slopes are nonetheless jagged and foreboding; climbing these is a mark of true intellectual achievement. But whether the way is smoothly paved or roughly made, the destinations are the same: small heights, little occupied. Those who reach these heights can rest secure. Out of humanity’s many billions there are only a handful of individuals who know their chosen domain as well as they do. They have mastered their mountain: they know its every crag, they have walked its every gully. But it is a small mountain. At its summit their field of view is limited to the narrow range of their own expertise.

In Washington that is no insult: both legislators and regulators call on the man of deep but narrow learning. Yet I trust you now see why a city full of such men has so little love for books. One must read many books, laws, and reports to fully master one’s small mountain, but these are books, laws, and reports that the men of other mountains do not care about. One is strongly encouraged to write books (or reports, which are simply books made less sexy by having an “executive summary” tacked up front) but again, the books one writes will be read only by the elect few climbing your mountain.

The social function of such a book is entirely unrelated to its erudition, elegance, or analytical clarity. It is only partially related to the actual ideas or policy recommendations inside it. In this world of small mountains, books and reports are a sort of proof, a sign of achievement that can be seen by climbers of other peaks. An author has mastered her mountain. The wonk thirsts for authority: once she has written a book, other wonks will give it to her.

The technologists of Silicon Valley do not believe in authority. They merrily ignore credentials, discount expertise, and rebel against everything settled and staid. There is a charming arrogance to their attitude. This arrogance is not entirely unfounded. The heroes of this industry are men who understood in their youth that some pillar of the global economy might be completely overturned by an emerging technology. These industries were helmed by men with decades of experience; they spent millions—in some cases, billions—of dollars on strategic planning and market analysis. They employed thousands of economists and business strategists, all with impeccable credentials. Arrayed against these forces were a gaggle of nerds not yet thirty. They were armed with nothing but some seed funding, insight, and an indomitable urge to conquer.

And so they conquered.

This is the story the old men of the Valley tell; it is the dream that the young men of the Valley strive for. For our purposes it shapes the mindset of Silicon Valley in two powerful ways. The first is a distrust of established expertise. The technologist knows he is smart—and in terms of raw intelligence, he is in fact often smarter than any random small-mountain subject expert he might encounter. But intelligence is only one of the two altars worshiped in Silicon Valley. The other is action. The founders of the Valley invariably think of themselves as men of action: they code, they build, disrupt, they invent, they conquer. This is a culture where insight, intelligence, and knowledge are treasured—but treasured as tools of action, not goods in and of themselves.

This silicon union of intellect and action creates a culture fond of big ideas. The expectation that anyone sufficiently intelligent can grasp, and perhaps master, any conceivable subject incentivizes technologists to become conversant in as many subjects as possible. The technologist is thus attracted to general, sweeping ideas with application across many fields. To a remarkable extent conversations at San Fransisco dinner parties morph into passionate discussions of philosophy, literature, psychology, and natural science. If the Washington intellectual aims for authority and expertise, the Silicon Valley intellectual seeks novel or counter-intuitive insights. He claims to judge ideas on their utility; in practice I find he cares mostly for how interesting an idea seems at first glance. He likes concepts that force him to puzzle and ponder.

This is fertile soil for the dabbler, the heretic, and the philosopher from first principles. It is also a good breeding ground for books. Not for writing books—being men of action, most Silicon Valley sorts do not have time to write books. But they make time to read books—or barring that, time to read the number of book reviews or podcast interviews needed to fool other people into thinking they have read a book (As an aside: I suspect this accounts somewhat for the popularity of this blog among the technologists. I am an able dealer in second-hand ideas).

I laugh sometimes at the complaints I see on humanities twitter bewailing the shallow reading habits of the tech-bro. The technology brothers read—a lot! I am sure more novels are read every year on Sand Hill Road than on Capitol Hill. Washington functionaries simply do not live a life of the mind. If Silicon Valley technologists do not always live such a life, they at least pretend to.

The upshot of all this is that books have an inordinate impact on the Silicon Valley mindspace. Often these books are stilted academic titles, works which at first glance have no obvious connection to software. “It’s interesting how Seeing Like A State has made it into the vague tech canon,” Jasmine Sun comments, “despite being from a random anarchist anthropologist who specialized in Southeast Asian agrarian societies.”1

“Vague tech canon” is a clever phrase. Siloed off on so many little mountains, I could not speak of a common DC canon, vague or otherwise. But for Silicon Valley the term is just—there are no formal canonizers in Silicon Valley, and thus no formal canon. But a “vague” canon, the sort that ties together any historical community of requisite intelligence and literacy, certainly exists. I challenged my followers on Twitter to try and define it.

I think it’s stratified by generation, but here’s an attempt. (This isn’t the list of books that I think one ought to read — it’s just the list that I think roughly covers the major ideas that are influential here.)2

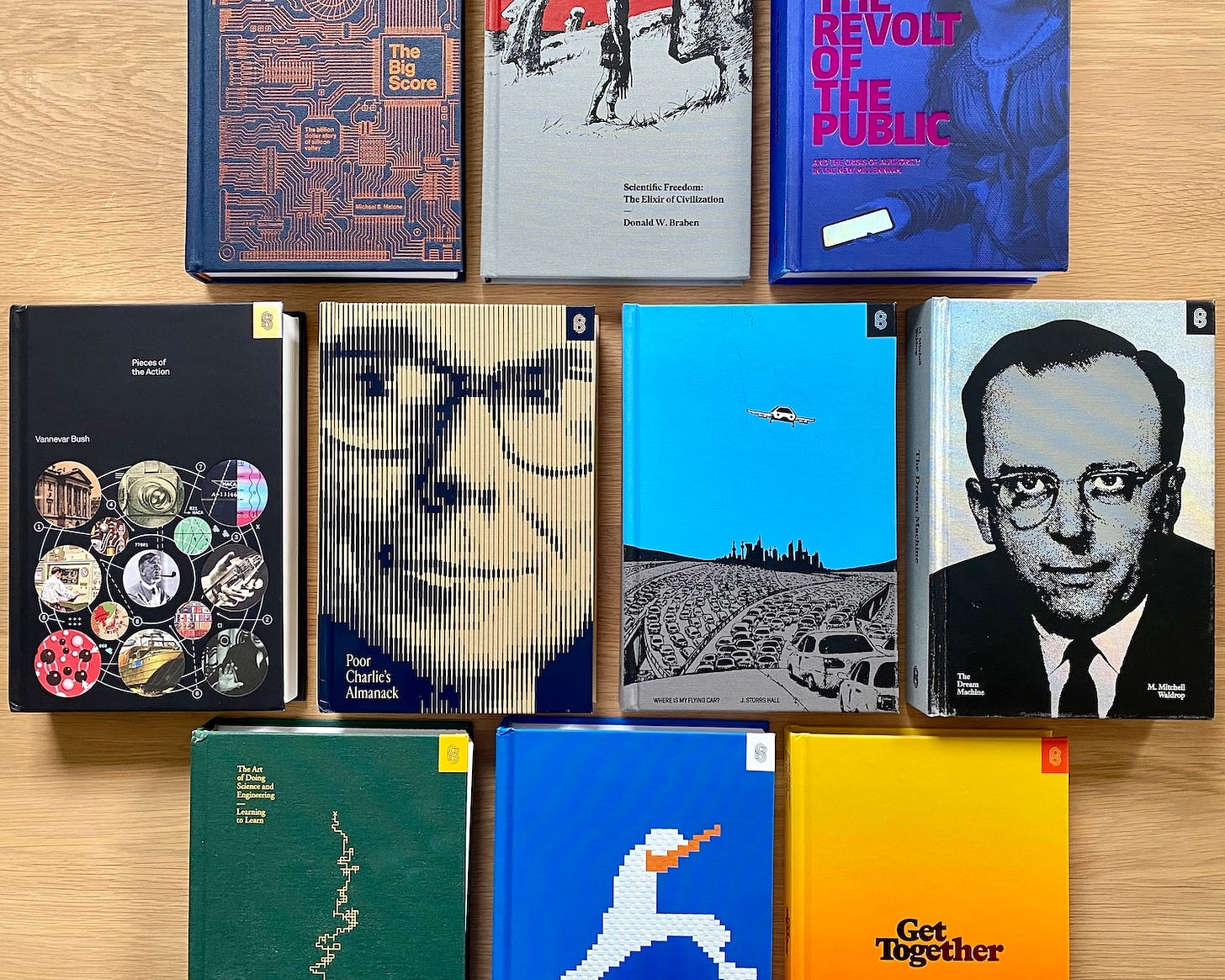

Here is the list that followed:

Asimov (1951), Foundation

Rand (1957), Atlas Shrugged

Brand (1968-1972), The Whole Earth Catalog

Brooks (1975), The Mythical Man-Month

Pirsig (1974), Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Caro (1975), The Power Broker

Dawkins (1976), The Selfish Gene

Alexander (1977), A Pattern Language

Card (1977), Ender’s Game

Hoftstader (1979), Gödel, Escher, Bach

Papert (1980), Mindstorms

Wolfe (1983), “The Tinkerings of Robert Noyce”

Ableson and Sussman (1984), Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs

Feynman (1985), Surely You're Joking, Mr Feynman!

Rhodes (1985), The Making of the Atomic Bomb

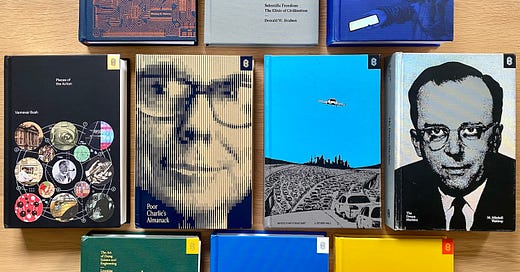

Malone (1985), The Big Score

Carse (1986), Finite and Infinite Games

Stephenson (1995), The Diamond Age

Rich (1996), Skunk Works

Graham (1998-2024), Essays

Scott (1998), Seeing Like a State

Raymond (1999), The Cathedral and the Bazaar

Hiltzik (1999), Dealers of Lightning

Davidson and Rees-Mogg (1999), The Sovereign Individual

Waldrop (2001), The Dream Machine

Morris (2001), The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

Symonds (2003), Softwar

Kushner (2003), Masters of Doom

Cowen (2003-2023), Marginal Revolution

Chernow (2004), Titan

Markoff (2006), What the Dormouse Said

Livingston (2008), Founders at Work

Meadows (2008), Thinking in Systems

Yudkowsky et. al. (2009-2024), LessWrong

Reis (2011), The Lean Startup

Herztfeld (2011), Revolution in the Valley

Deutsch (2012), The Beginning of Infinity

Jackson (2012), The PayPal Wars

Alexander (2013-2024), Slate Star Codex/Astral Codex Ten

Bostrom (2014), Superintelligence

Thiel (2014), Zero to One

Horowitz (2014), The Hard Thing about Hard Things

Zachary (2014), Showstopper

Gordon (2016), The Rise and Fall of American Growth

Vance (2017), Elon Musk

Wiener (2020), Uncanny Valley

(Note: I have edited Collison’s list to include years, and re-ordered it chronologically).

Brian Armstrong adds these titles to Collison’s list:

Grove (1995), High Output Management

Collins (2001), Good To Great

Kurzweil (2005), The Singularity is Near

Wu (2010), The Master Switch

Thorndike (2012), The Outsiders3

Dozens of other people responded; some of the common titles from these responses include Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations and other Stoic literature, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Douglas Adams’ Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma, Andy Weir’s The Martian, Iain Banks’ The Player of Games, William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow, Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Black Swan or Anti-Fragile, Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs, Venkatesh Rao’s Ribbonfarm essays, and various titles by Rene Girard.

You can divide most of these titles into five overarching categories: works of speculative or science fiction; historical case studies of ambitious men or important moments in the history of technology; books that outline general principles of physics, math, or cognitive science; books that outline the operating principles and business strategy of successful start-ups; and finally, narrative histories of successful start-ups themselves.

I do not think the average Silicon Valley founder has read all of these titles. But enough of them have read, say, Chernow’s Titan, or Rhodes’ Making of the Atomic Bomb, that the rest of them might be expected to have something intelligent to say about John Rockefeller or Robert Oppenheimer if the topic comes up over the dinner table.

The focus on biographies does not surprise me. There is an implicit “great man” (or “great team”) theory of history behind the vague tech canon. But I do not think Silicon Valley readers are drawn to these histories and biographies because of the light they shed on historical processes, or even some deep-seated belief in the primacy of agency over structure. The attraction feels more primal to me—or perhaps more classical. Here is how Plutarch, classical biographer par excellence, described his attraction to the stories of great men:

We may say, then, that achievements of this kind, which do not arouse the spirit of emulation or create any passionate desire to imitate them, are of no great benefit to the spectator. On the other hand virtue in action immediately takes such hold of a man that he no sooner admires a deed than he sets out to follow in the steps of the doer. Fortune we prize for the good things we may possess and enjoy from her, but virtue for the good deeds we can perform: the former we are content to receive at the hands of others, but the latter we desire others to experience from ourselves. Moral good, in a word, has a power to attract towards itself. It is no sooner seen than it rouses the spectator to action, and yet it does not form his character by mere imitation, but by promoting the understanding of virtuous deeds it provides him with a dominating purpose.4

The classical historian did not think in terms of “historical processes” but in terms deeds—great deeds, the sort of deeds that brought glory or shame to the doer simply by being done.5 Perhaps you see the connection between this conception of history and the lengthy epigraph at the topic of this post. Each Greek polis was united by a common set of moral ideals. These were often taught formally, but the most important education came from observation, not instruction. The distribution of power and honor within a polis was itself an education in character. By observing who was allowed power and honor, and how the powerful and honored comported themselves in the affairs of their city, the youth of each polis learned what it meant to be a good man and live a good life in their community.6 Thus the structure of rank and honor (políteuma ) and the moral formation of the citizen (paıdeía) were one and the same.

The historian and biographer extends this backwards in time. Now youth find models of honor not only among the living but among dead. To study the great men of a community’s past is to study what greatness means in that community. That I think is half the purpose of these biographies of Roosevelt and Rockefeller, Feynman and Oppenheimer, Licklider and Noyce, Thiel and Musk. These books are an education in an ethos. Such is the paıdeía of the technologists.

————————————————————-

Your support makes this blog possible. To get updates on new posts published at the Scholar’s Stage, you can join the Scholar’s Stage Substack mailing list, follow my twitter feed, or support my writing through Patreon. If you found this post worth reading, you might find some of my other essays on science, technology, and modern life worth reading. In addition to the pieces written linked to above, check out “Uber makes a Poor Utopia,” “American Nightmares: Wang Huning and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Dark Visions of the Future,” “Has Technological Progress Stalled?,” “Thoughts on Post Liberalism,” and “Lessons from the 19th Century.”

—————————————————————-

Noah Putman, “The Concrete Oasis,” Reboot (18 August 2024). Jasmine, as editor of Reboot, made this comment on Putman’s essay below the fold.

Plutarch, The Rise and Fall of Athens: Nine Greek Lives, trans. I Scott Kilvert (New York: Penguin, 1991), 166.

On this point see Hannah Arendt, “The Concept of History” in Between Past and Future (New York: Viking Press, 1961), 41-72.

Rahe further explores this point, and its relevance to modern politics, in Republics Ancient and Modern, 3 vols (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

Thanks for this insightful article. It’s illuminating to see that, except for the stoics, the entire canon consists of 20th—or 21st-century books. In other words, it skips what is traditionally called the history of ideas, let alone potentially retarding ethics or hard-to-read epistemology (like Kant or Wittgenstein). Why? I guess because it presupposes that these books are either outdated or of no use for the purpose of disruption. The reading (or skimming or even just listening) habits aim to move fast and not get lost in complicated, let alone abysmal thoughts.

Robert Caro's The Years of Lyndon B. Johnson series is missing...(and belongs on the list imo)