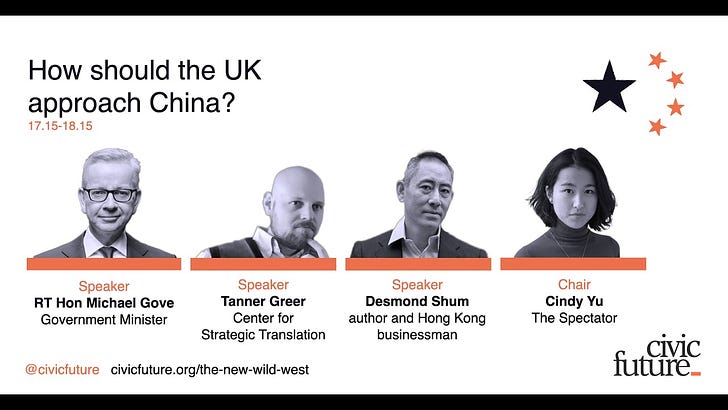

Last month Civic Future invited me to join a panel at their annual policy forum. The topic: what the United Kingdom should do about China. As I am neither a British citizen nor an expert in British affairs, I thought it impolitic to lecture my hosts on how they should be governing their own country. Instead I focused my remarks on the communist government in Beijing. My aim was to lay out several elements of Chinese foreign policy that must be taken into account by statesmen from any Western country.

It will be difficult to guide any nation through the storms of the next two decades; it will be harder still if our leaders chart their course without reference to the fundamental ways, means, and ends of Chinese strategy. These ways, means, and ends are discernible. When you clear out the deadwood and the underbrush you will find that the many branches of Chinese foreign policy spring from only a few trunks, each vital and deep-rooted.

Others might parse the fundamentals of Chinese grand strategy slightly differently. What follows is my personal attempt to summarize the essentials of Chinese foreign policy in as few points as possible. These can be stated as follows:

The overriding goal of the Communist Party of China is to restore China to a position of glory and influence commensurate with its ancestral heritage.

This can only be accomplished by pioneering a technological transformation of the global economy on the scale of the industrial revolution.

The greatest perceived threat to China’s rise is found in the ideological domain—and in a globalized world that domain is a global one.

Chinese leaders imagine they will reshape the global order primarily through economic, not military, tools.

The main exception to this is Taiwan. With Taiwan economic tools have proven ineffective; the possibility of war is very real.

As I was limited to only eight minutes speaking time, I did not explore all five of these elements at great length. I decided to focus on points #1 and #3, which struck me as the most immediately relevant to the British state. However, I have explored most of the others in various essays I have published over the last few years.

Those who would like to read my assessment of the singular role that technology plays in Chinese grand strategy should read the essay Nancy Yu and I published in Foreign Policy earlier this year: “Xi Believes China Can Win a Scientific Revolution.” (For those locked out behind a paywall, I excerpt a key paragraphs and expand my argument in my follow up blog post, and summarize my arguments on Bonnie Glaeser’s podcast China Global).

I have written a great deal about Chinese perceptions of threat and the relationship between their threat perceptions and their foreign policy. My best attempts to tackle the topic succinctly are my two contributions to the Lowy Institute round-table on a Chinese world order.

I outline the role Communist leaders believe that economic integration will play in advancing their nation to “the center of the world stage” in my 2020 essay for Palladium, “The Theory of History That Guides Xi Jinping.” (The economic situation has changed somewhat in the years that followed. I analyze how these changes have impacted both Party theory and strategy here and here).

Finally: I have not yet written a piece that explains, with proper sourcing, why I believe the Chinese leadership will be willing to resolve the Taiwan problem through force of arms. I do describe the basic strategic dynamics at play, however, in the essays “We Can Only Kick Taiwan Down the Road So Far” and “Sino-American Competition and the Search For Historical Analogies.”

A video of my opening statement, as well as the prepared statements of the other two panelists and our responses to the questions from the audience, has been embedded at the top of this post. You can also find it here, on the Civic Future Youtube channel.

—————————————————————————————

For more of my writing on geopolitics, you might also like the posts “Sino-American Competition and the Search for Historical Analogies,” “Against the Kennan Sweepstakes,” “Of Sanctions and Strategic Bombers,” “Fear the First Strike,” “The Lights Wink Out in Asia,” and “Losing Taiwan is Losing Japan.” To get updates on new posts published at the Scholar’s Stage, you can join the Scholar’s Stage Substack mailing list, follow my twitter feed, or support my writing through Patreon. Your support makes this blog possible.

————————————————————————————–

I have long admired and learned from your posts, but this one is questionable.

The points you make about China’s grand strategy (foreign policy) are fine, esp. for China as a nation-state. They cover the standard political, economic, and military categories normally used for analyzing nation-states.

However, China’s leaders now regard China as a civilization-state too. They want China to be viewed and treated as such, and are developing policy and strategy fundamentals to advance as a civilization-state. I’m finding that nearly all U.S. experts on China have ignored or dismissed this turn. But if it’s for real (as I think it is), it will mean that U.S. analyses of China’s grand strategy (foreign policy) would benefit from adjustments.

Civilizations, more than empires and nations, are defined primarily by their cultural contents, broadly defined. From what I gather, adopting a civilization-state moniker means upholding one’s identity in terms of the cultural values and formative traditions that are said to define a people, thereby determining their ways of life and their beliefs in themselves as a collectivity, no matter where they reside. Accordingly, collective identity trumps individual identity; spiritual values are more defining than ideology; and cultural heritage and tradition matter mightily.

I’m no China expert, but Xi’s regime sure looks to be going in that direction. It’s even developing concepts about cultural sovereignty and cultural security. If so, adding a cultural fundamental to the your list of strategy/policy fundamentals would seem advisable. To some extent, my point is embedded in your allusions to glory, heritage, and ideology — but not clearly or strongly enough.

Accordingly, you write, “4. Chinese leaders imagine they will reshape the global order primarily through economic, not military, tools.” That’s a kind of point I typically see in U.S. analyses these days. But it overlooks seeing that, by thinking and acting as a civilization-state, China is using cultural tools too. It would be more accurate to write that “Chinese leaders imagine they will reshape the global order primarily through cultural and economic, not military, tools.”

I remain baffled that China’s civilizational thrust is so widely disregarded and shrugged-off by U.S. experts on China. It seems part of China’s long game, and might offer new angles for getting along (or not?).

One quibble: Your post is about “the fundamentals of Chinese grand strategy” but then lays out “the essentials of Chinese foreign policy.” Grand strategy and foreign policy are not the same, though they overlap. I’m sure you know this. Maybe keep in mind for next write-up.

Wishing that you would present an argument about the military threat to Taiwan at some point in the foreseeable future. To my mind, as to many others, it's less than self-evident.

As for your first point, "the natural role of China being to be the center of human civilization", it is impressive how ambiguous it remains for all these years, even among scholars i.e. people who make a claim on rigor.

For example, you say the goal is to "restore China to a position of glory and influence commensurate with its ancestral heritage," which leads to the question of : What IS commensurate to its heritage in today's world?

Adding to it, even the historical role of China in its region remains a subject of controversy, with its symbolic as well as material domination being disputed https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29WJ3sZup-U .

But let's leave that aside, as China's leadership of today has specific goals about what to dominate.

Those goals must be based on deeply seated symbolic reasoning, closely related to a sense of insecurity about one's place in the world. And, they must also be based on what we customarily call 'science,' where claims are rigorously checked against systematic observations. Then the question arises: How do these two components interact with each other?

...

My foremost suspicion is about the tendency of every observer, including Western observer, to project their own attitudes to the world onto China. But since that topic leads to handwaving easily. So, let's be specific :

You say China's leaders will see the West as an existential threat for as long as the West insists on certain values, including "democracy is being described as a universal good by Western leaders." Wait a minute: democracy is being described as a universal good by Chinese leaders, too. That's a weak point in what you say. As for liberal values, ... a good proportion of Western voices perceive liberal values as threatening to the West itself. As for Western protection of voices hostile to the Chinese leaders: well, let's look at China's protection of voices hostile to Western leaders. Perhaps a topic for another time.