Republican Debates on China: A Political Compass for Potential Trump Appointees

A Preliminary Taxonomy

MANY HAVE TRIED to pin Trump to Heritage’s “Project 2025.” The Trump campaign has not only refused to endorse Project 2025—they have refused to endorse any detailed policy plan whatsoever. Trump prefers to keep his options open.

One unanticipated benefit of this approach is that Republicans have spent much of the last year engaged in intensive but open debates over policy. Ambitious politicians, congressional offices, and think tanks have laid out their preferred plans on almost every issue of importance. These plans often differ from each other in striking ways. Absent endorsement from Trump or his campaign, no one quite knows which of these policy packages will eventually be adopted as the Republican standard. The Republicans involved have thus been free to debate the merits and costs of each.

Take China policy.

I have spent much of the last month and a half interviewing Republican politicians, staffers, think tankers, and the like on their preferred approach to China. These interviews are still on-going. While my full findings will be published in a report for the Foreign Policy Research Institute later this year, the Institute has published a pre-election teaser of my larger report this week. The focus of this teaser is on the geopolitical debate. This is important, because there are actually two debates about China. The first is focused on the economic challenge of a rising China; the other is focused on geopolitics. As I put things in my essay:

It is common for individuals to be closely allied in the economic sphere but not in the geopolitical sphere, or vice versa. For example, senators Marco Rubio and J.D. Vance are close allies on the economic front; there are few meaningful distinctions between the economic strategy each endorses. Their respective takes on the geopolitical problem posed by China are much harder to reconcile.

In theory, one’s position on the CHIPS Act or tariff rates might influence one’s position on military commitments to Taiwan or military aid to Ukraine. In practice, this is rarely so. The economic and geopolitical debates occur on different planes.

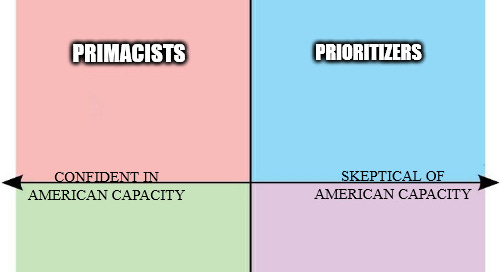

Currently, I think a four-quadrant “political-compass” is a useful way to make sense of the geopolitical debate (see the image at the head of this post).

One axis is a measure of optimism vs. pessimism:

Where one falls in many of the most prominent debates—such as “Can the United States can afford to support both Ukraine and Taiwan?” or “Should the ultimate goal of our China policy be victory over the Communist Party of China, or should it be détente?”—has less to do with one’s assessment of China and more to do with one’s assessment of the United States. What resources can we muster for competition with China? Just how large are our stores of money, talent, and political will?

Those on the right quadrants of my diagram provide pessimistic answers to these questions. They buttress their case with measurables: steel produced, ships at sea, interest paid on the federal deficit, or the percentage of an ally’s gross domestic product spent on defense. Against these numbers are placed fearsome statistics of Chinese industrial capacity and PLA power. Changes in technology, which favor shore-based precision munitions at the expense of more costly planes and ships, further erode the American position. This is a new and uncomfortable circumstance. The last time the United States waged war without overwhelming material superiority was in 1812.

To those who see American power through this frame, there is only one logical response: the United States must limit its ambitions. This means either radically reprioritizing defense commitments to focus on China or retreating from conflict with China altogether.

Those on the left two quadrants see things differently. Where the pessimists see settled facts, the optimists see possibilities. The optimists recognize many of the same trends as the pessimists, but view them as self-inflicted mistakes that can, and should, be reversed. An inadequate defense budget is not a law of the universe but a political choice. If Trump wins, he will choose otherwise. Implicit in the optimist view is a longer time horizon—there is still time to turn things around. But this window will not be open forever. Optimists fear that pessimistic assessments erode the political will needed to make changes while change is still possible.

…In their debates, the pessimists are quick to highlight the few weapons systems being shipped across the Atlantic that might be used in the Pacific, but their critique reaches higher than this. The costs of the war in Ukraine (and the Middle East) are measured not just in bullets, but in attention and effort: There are only so many minutes the National Security Council may meet. Washington can only have a few items on its agenda at any given time. The executive branch is stodgy, slow, and captive to bureaucratic interests; the legislative branch is rancorous, partisan, and captive to public opinion; the American public does not care a whit about the world abroad. Accomplishing anything meaningful in the United States—much less the drastic defense reforms both sides of the debate agree are necessary—requires singular attention and will.

If this seems like a pessimistic take on the American system—well, it is one. It is common for people in the optimistic quadrants to argue that the People’s Republic of China is riddled with internal contradictions. In a long-term competition between the two systems, they are confident that these contradictions will eat China from the inside out, and that America’s free and democratic order will eventually emerge victorious. None of the pessimists I interview make similar predictions. If they have anything to say about internal contradictions, it is American contradictions they focus on.

My y-axis, on the other hand, presents two poles of argument, one focused on power and the other focused on values:

Republicans in the top two quadrants ground their arguments in cold calculations of realpolitik. From this perspective, international politics is first and foremost a competition for power. States seek power. The prosperity, freedom, and happiness of any nation depend on how much power its government can wield on the world stage. While states might compete for power in many domains, military power is the most important. A state frustrated by a trade war might escalate to a real war, but a state locked in deadly combat has no outside recourse. The buck stops with the bullet.

From the power-based perspective, then, the goal of American strategy must be the maximization of American power, with military force as the ultimate arbiter of that power.

The lower two quadrants, in contrast, are populated by those who “believe that American foreign policy should not be evaluated by a single variable. They see connections between what America does abroad and what America is like at home. They have strong values-based commitments to specific ways of life that are expressed in their vision for American strategy.”

These two groups do not mirror each other as easily as the people in the upper quadrants. In theory a primacist in the upper left could become a prioritizer in the upper right if he was convinced of American weakness. The bottom two quadrants, however, do not just differ in their perception of American strength, but also in the particular values espoused.

I have labelled those in the bottom left quadrant “internationalists” because of how often they invoke the phrase “liberal international order.” This group believes that America and its allies are knit together not only by shared security interests, but also by shared values. In fact, the values shared by the liberal bloc explain why these countries share security interests in the first place. China is an authoritarian power whose influence operations threaten the integrity of democracies across the world. Many internationalists view this political-ideological threat as the most dangerous that China poses. Those in this quadrant are especially skeptical of détente; they do not believe permanent compromise with China is possible. They attribute Chinese belligerence to the communist political system that governs the country. For them, tensions in U.S.-Chinese relations are less the expected clashes between a rising power and the ruling hegemon than a battle between two incompatible social systems. Pointing to the close cooperation that ties Iran, North Korea, Russia, and China together, the internationalists argue (contra the prioritizers) that the world is gripped in a general contest between liberal order and resurgent authoritarianism whose different parts cannot be disentangled from each other.

Those in the bottom right quadrant—the restrainers—also think about foreign affairs through a regime lens, but the belligerent regime in question is their own. Republican restrainers link the liberal international order to the free trade agreements all Trumpists despise and the administrative “deep state” all Trumpists distrust. They see the liberal international order as an international extension of the progressive order they are trying to tear down at home.

If you want to get a sense for where specific individuals might lie on this compass, here is an altered version of the compass I made a week ago:

I am less confident in the exact placing of these individuals/institutions than I am in the larger quadrant-categories. Just how close JD Vance is to the restrainer line, or how far Marco Rubio is from the arguments of the primacists, is difficult to tell (there are no scientific units for either the x or the y, and politicians will shift with circumstance). But these two men, close allies on the economic front, are in opposite quadrants. Only someone in the bottom left quadrant would draft the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act. That is not a bill I can imagine Vance, or any other prioritizer, bringing to the Senate Floor.

Whether Vance is actually a prioritizer, or whether he simply presents as one, was disputed by those I interviewed. This has been one of the most surprising themes of my interviews. People on both sides of the compass often questioned whether those on the other side were being honest with the true reasons for their arguments:

Again and again I heard this accusation made: prioritizer arguments are just an attempt to make isolationism sexy. The prioritizers do not actually believe in realpolitik—realpolitik is just a respectable way to attack the existing international order they despise.

There is an irony to this critique. Just as primacists and internationalists condemn the false face of the prioritizers, so the prioritizers and the restrainers condemn the false face of the primacists! Many of those I interviewed insisted that their primacist opponents made such-and-such argument not for the realpolitik reasons they professed, but because of their (hidden) commitment to liberal ideals. Ideals that cannot be defended on their own merits had to be prettied up with talk of hard power.

All of these suspicions of subterfuge are overblown. Both primacists and prioritizers believe the arguments they make. Yet their suspicions are revealing! All sides clearly believe there is political advantage in couching one’s arguments in realpolitik logic. That fact alone tells us something about the likely contours of a Trump presidency—and perhaps the beliefs of Trump himself.

Read the full thing over at FPRI.

—————————————————————————————

For more of my writing on geopolitics, you might also like the posts “Sino-American Competition and the Search for Historical Analogies,” “Against the Kennan Sweepstakes,” “Of Sanctions and Strategic Bombers,” “Fear the First Strike,” “The Lights Wink Out in Asia,” and “Losing Taiwan is Losing Japan.” To get updates on new posts published at the Scholar’s Stage, you can join the Scholar’s Stage Substack mailing list, follow my twitter feed, or support my writing through Patreon. Your support makes this blog possible.

————————————————————————————–

These are close to my four quadrants, which in turn are based on Walter Russell Mead's four strands of American foreign policy. https://arnoldkling.substack.com/p/where-do-you-stand

Elon Musk? He seems off the map