Inside the Mind of Wang Huning; Christmas Day as Judgement Day

China's Most Powerful Intellectual Describes the Source of American Greatness

Wang Huning on American Technology and American Greatness

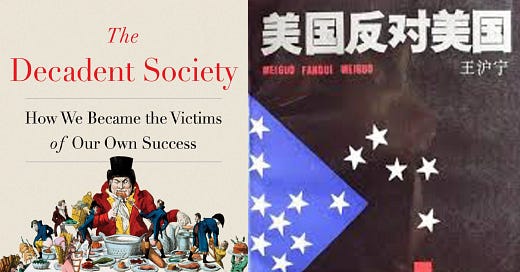

Wang Huning, fourth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee, has served as China’s ideologue-in-chief for the past two decades. He has been called the “world’s most dangerous thinker” and the “éminence grise” of Xi Jinping. The Center for Strategic Translation has published two translated excerpts from his book America Against America in November. I wrote an essay in response to these pieces at the Scholar’s Stage: “Wang Huning and the Eternal Return to 1975.”

Wang visited the United States when he was a young, up-and-coming professor of political science in China. The book is one part travelogue, one part philosophical meditation. Visiting America at a time when China was still poor and undeveloped, Wang is astonished by the cars, computers, and cityscapes he sees in the United States. In the first section of the book, Wang asks why the United States became a technological super power:

Anyone who comes to the United States will feel a sort of “future shock.” [In this situation], one type of person will just think about how they can enjoy being in America; another type of person will ponder why there is an America. ...What forces created such an awe-inspiring material civilization? What administrative and intellectual systems created the conditions for this development? Is this end-state the result of chance, or was it a historic inevitability?”

In the second translated section of the book Wang provides one answer: the Americans have a rare relationship with the future. In America, futurism and innovation do not stand opposed to American traditions—they are the essence of American tradition. America’s pioneer experience has imbued the American character with a fascination with worlds unseen. This attraction to the future, Wang maintains, is one of the few ideals more powerful than commercialism and greed, the one countervailing force in American life strong enough to moderate the atomizing tendencies of modern capitalism.

Wang’s thoughts are interesting, and worth reading in full. In my essay I contrast Wang’s perception of 1980s America with the America portrayed in Ross Douthat’s book The Decadent Society. If Wang describes innovation as a foundational part of the American character, Douthat faults America for innovating too little. I suggest that Douthat’s story begins just where Wang’s ended:

[Wang] sees evidence of American futurism everywhere he looks: in the science fiction blockbusters Americans watch, in the ambitious urban planning committees of American cities, in farsighted Pentagon budgeting and base building, in the money Americans pump into the university education system, and in the fantastic engineering marvels Americans build. Wang specifically points to the Strategic Defense Initiative (aka. Reagan’s Star Wars program), the Texas based Super-Conducting Super Collider, and the Biosphere 2 research facility as three contemporary examples of Americans’ willingness to pour resources into outlandish ventures that promise a glimpse at a better future.

But wait—the Strategic Defense Initiative did not produce any technological breakthroughs before Congress closed the program down in 1993. The Super Collider was never finished. Biosphere 2 is now a museum. University budgets are being cut across the country. The U.S. Navy now faces terrible crisis precisely because of the Pentagon’s unwillingness to budget for the future. Urban planners are tied down by unshakable vetocracy. The science fiction blockbusters of the last decade are all sequels or remakes of the blockbusters of yesteryear.

In many ways, the cultural traits that Wang celebrates as key to America’s success now describe Chinese society better than American society. This is a disturbing conclusion—read it in full HERE.

Christmas Day as Judgement Day

My most recent essay journeys through the Christmas celebrations of my youth. We tour my grandmother’s 12 Christmas trees, the Christmas I was forced to haul cans of food to families in need in a frigid Minnesotan storm, and the shallow and commercial Christmases of East Asia. I reminisce for a reason. “The Christmas season,” I argue, “is a sort of measuring stick. What is good in bourgeois civilization is concentrated in this season of beauty and merriment. Against this bar all creeds, all claimed paths to excellence, all cults of eudaimonia, may be measured. Against this bar most are found wanting.”

There is nothing heroic, nothing daring or brave in my childhood Christmas stories. Nothing in my Christmas past embodies justice or even wisdom; these were not moments of transcendence or enlightenment. But it is impossible for me to wade through this stream of memories without concluding that these were moments where I met the good.

For me, at least, this suggests something important about what goodness is, how it can be measured, and how it must be sought:

[Christmas] is silly and sentimental, a thoroughly domesticated holiday, in practice a celebration of the most bourgeois aspects of life: private happiness, familial bliss, childhood as a privileged category, contentment derived from creature comforts, joy derived from things given and received, and charity as the guiding virtue—but charity practiced soul-to-soul, not at the level of society as a whole. It is not a holiday that celebrates justice, nor greatness, nor ambition; it is mirthful but never Dionysian; it is faithful but never austere. It sits uneasy with the ethos of the conqueror; it fits no better in the theorizing of the philosopher. No Greek nor Roman, no crusader nor hermit, no revolutionary, no terrorist, no underground man can smile sound on this Victorian relic.

This holiday does not idolize excellence. It gives equally to the old, the poor, and the ugly. It does not ask for supreme sacrifices. It does challenge those who celebrate it to recognize the supreme sacrifice of another—but to recognize this sacrifice in an everyday way, through modest and moderate acts of goodwill. It is a celebration well made for the temperate. It defines success as sitting around the mantel piece, kids in tow. It draws meaning from nostalgia and merriment, in small rituals and small acts of kindness. Christmas is a bundle of unapologetically mawkish sensibilities gone wild—and despite all of that, it is good.

Read the rest of my Yuletide reflections HERE.